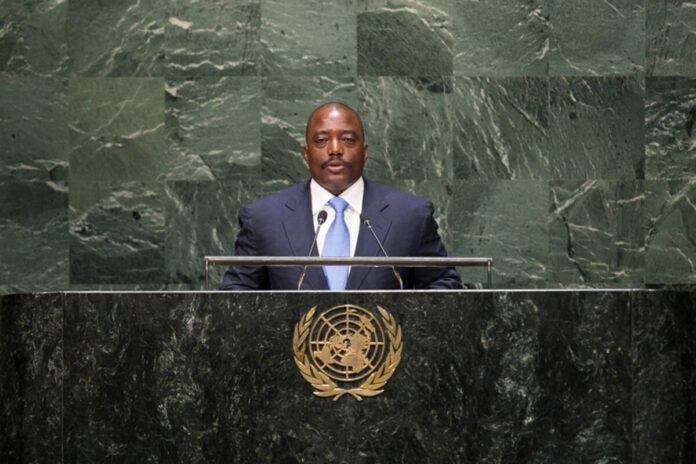

Recent disclosures have unveiled a complex network of covert equity stakes and financial manoeuvres linked to former Congolese president Joseph Kabila, shedding light on the mechanisms of post-presidential rentier capitalism in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Leaked materials, have brought to light the financial legacy of Joseph Kabila, who served as President of the DRC from 2001 to 2019. Central to these revelations is Fortunata “Tina” Ciaparrone, an Italian entrepreneur based in Kinshasa, who admits to acting as a nominee shareholder for Kabila. According to Ciaparrone, Kabila holds a 25% equity interest in several companies, including SOGEMIP Mining (cobalt, lithium, copper, manganese), CIIG, Coete Gaz, SOTEXKI, and Texico. Although officially 100% owned by Ciaparrone, she states on video that “25% belongs to Mr. Kabila,” suggesting an institutionalized system of hidden participation—a customary cut for proximity to power.

Financial Engineering and Shell Structures

One of the more revealing sequences involves a single-day round-trip transaction involving SOGEMIP and a company called LIU Resources, purportedly designed to launder USD 8 million. The transaction entailed SOGEMIP “investing” 35% into LIU Resources, selling those same shares back within 24 hours, generating an unexplained $8 million capital flow. This mimics a classic laundering operation: capital injection without real underlying economic activity, followed by a controlled exit to legitimize previously untraceable funds. The transaction’s timing, lack of public record, and absence of financial disclosure from SOGEMIP raise questions about internal audit procedures and AML/CFT compliance.

Strategic Assets and Non-Transparent Ownership

SOGEMIP is not a marginal player. It holds stakes in oil blocks alongside PERENCO and ENI, including N’DUNDA, Yema, Matamba, and Makanzi. According to former hydrocarbons minister Didier Budimbu, these reserves may total $15 billion in extractable value. The alleged 25% ownership by Kabila could translate into hundreds of millions in long-term earnings. In addition, SOGEMIP Mining operates in Lualaba, one of Africa’s richest corridors for critical minerals—especially cobalt, which is essential for EV battery supply chains. These revelations create material reputational and legal risk for foreign partners and lenders who fail to perform enhanced due diligence on politically exposed persons and their networks.

Regulatory Breakdown and State Capture

What’s most concerning is not just the illicit enrichment—but the total absence of regulatory reaction: no judicial inquiries have been launched, no asset declarations or beneficial ownership disclosures are enforced, and no banking suspicious activity reports appear to have been filed. The implications go beyond governance. They reflect a de facto privatization of resource governance, in which access to state concessions is conditional on unofficial equity transfer—what could be considered a “presidential tax.” This undermines the core objectives of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, to which the DRC is formally committed.

Implications for Compliance, Investment, and ESG Risk

For investors and financial institutions, the Kabila revelations raise three immediate red flags: the lack of beneficial ownership registries in the DRC leaves firms exposed to hidden politically exposed person interests; any agreements signed with entities under such informal influence risk future invalidation under anti-corruption clauses; and for ESG-focused investors, these patterns constitute direct violations of governance standards and social safeguards. The DRC remains a frontier market with commodity upside, but one where regulatory opacity and elite capture generate unquantifiable tail risks.

Toward Systemic Reform

The “25% model” attributed to Joseph Kabila is not simply an indictment of one individual’s misconduct—it’s a blueprint for how informal political capital is converted into economic capital in fragile states. It thrives on the absence of enforcement, the complicity of gatekeepers, and the indifference of institutions. For international financial actors, this underscores the need to demand full beneficial ownership transparency from Congolese counterparties, implement mandatory politically exposed person screening for all extractive-related deals, and support capacity-building in Congolese financial oversight bodies. Without these, the Congo’s wealth will continue to flow—just not to its people.

UK-Based ESG Funds at Risk

Moreover, ESG-conscious asset managers headquartered in London may unknowingly hold indirect stakes in DRC ventures tainted by hidden political ownership. Given the UK’s prominence in sustainable finance, this raises compliance issues related to the FCA’s Sustainability Disclosure Requirements and greenwashing scrutiny from stakeholders.